-

Painting Outdoors, or en plein air as it’s known, is making a comeback.

We’ve noticed plein air communities and competitions springing up everywhere of late. The growing resurgence could be attributed to the pandemic, which saw a greater number of artists venturing outside to paint, rather than sticking to their usual studio-based routine. People in general are seeking communities more than ever, as a respite from isolating environments or working from home. This could include wild swimming clubs, running clubs, walking groups and painting groups.

We know that being outdoors has so many health benefits and it’s a welcome challenge for most artists. It harks back to a more simplistic – or should we say purist? – approach to life, rather than being stuck to a screen 24 hours a day. Painting outdoors requires your complete focus, overcoming both practical and physical challenges. We asked oil painter Georgina Potter for her top tips, ‘if you’re serious about painting plein air, you need to get out in all weathers. I always stand on cardboard to keep the cold at bay.’

This year, we are delighted to launch Wimborne Plein Air – an exciting open painting event for the May Bank Holiday weekend, intended to inspire budding plein air artists in three categories; Professional, Amateur and 14 – 18 year olds. Since opening the gallery last year, we’ve been adding more and more opportunities for art lovers and collectors to get involved. As well as an exciting programme of exhibitions, Saturday Socials, the Artists Society, Young Artist of the Year award and a new studio for workshops, we wanted to bring a live painting event to the heart of the town. When respected oil painters Maria Rose and Tom Stephenson agreed to be judges, the course was set.

It's only £20 to enter online and is open to emerging and more experienced artists alike. Everyone is welcome – we want to see what talent is out there and give you the opportunity for exposure, validation and the chance to win some amazing prizes.

John Constable pioneered a plein air approach to painting in the early 19th century, then from 1860 onwards it became fundamental to the Impressionist movement which brought it into the mainstream. Artists belonging to the Hudson River School took this style of painting very seriously and the Luminists almost deified Mother Nature – her forests, mountains and wildlife. Before this time, it would have been unthinkable that paintings sketched outdoors were nothing more than preparatory studies.

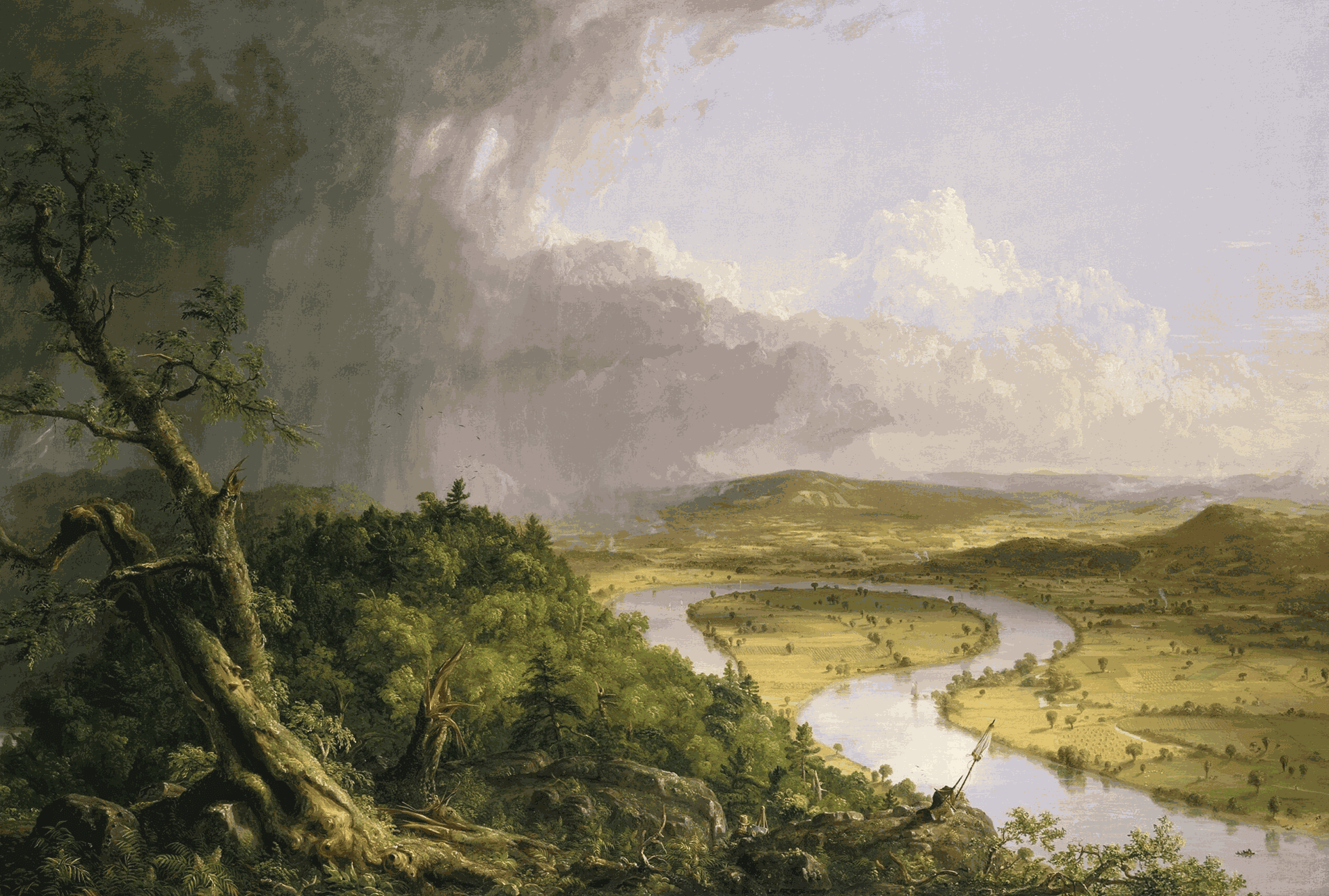

Example of Hudson River School: Thomas Cole (1801–1848), The Oxbow, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm (1836)

Developments in art materials, the advent of paint becoming available in tubes or pans (paint cakes) in around the 1870’s, plus portable easels that were more lightweight than their earlier counterparts, suddenly made it possible to paint outside. Before this, artists made their own paints by griding pigments with oils – it was a messy business! ‘The Golden Age of Watercolour’ from the mid 18th to mid 19th centuries was an explosion of interest by amateurs who started to take up the activity as a hobby. Watercolours provided the ideal medium, lightweight and minimal – among the aristocratic classes, painting was considered an important adornment of a ‘proper’ education. En plein air carrying cases, or pochades, are described as early as 1731 as ‘constructed of mahogany and fitted with brass hardware and embossed-leather linings, providing porcelain mixing pans, wash bowls, storage tins for chalks or charcoals, trays for brushes and porte-crayons, scrapers, blocks of ink and colours.’

William Reeves, an 18th century colourman, was awarded the Silver Palette of the Society of Arts for his invention of the ‘paint cake’ in 1781. These small, hard cakes of soluble watercolour were revolutionary. By the 1830’s artists could buy watercolours in porcelain pans, before further advancements in 1842 produced the first watercolours in collapsible metal tubes, thanks to Winsor & Newton. They set an international standard with their consistently high machine-ground pigments and they were granted a Royal Warrant in 1841. Before long, artists could liberally wash their paper with vivid colours never used before in this way – early critics were proved very wrong indeed!

William Winsor and Henry Newton were already working alongside some of London’s well known colour-men who procured rare pigments from across the globe and congregated in the artists quarter around Rathbone Place, central London. Indeed Constable, a neighbour, was one of their early customers. New compounds that were suddenly affordable, such as cerulean, chrome orange and cadmium yellow minimised time spent grinding and mixing with a pestle and mortar in the studio! The pocket sized ‘Shilling Colour Box’ – a lightweight japanned tin with pan colours and mixing palettes became a Victorian best seller, selling more than eleven million units between 1853 and 1870. The dye was cast, and painting plein air in watercolour has remained fashionable ever since.

A shilling box

The rural naturalists took this style of painting as an important technical approach to naturalism. The Newlyn School of Art was a major proponent of the technique in the later 19th century. Here is a picture of Stanhope Forbes who painted in extreme conditions, often tying down his easel with guide ropes on the beaches around Cornwall where he would paint.

David Hockney, the grandfather of modern plein air painting, exhibited his Grand Canyon works in the 90’s and the famous Yorkshire landscapes in the 2000’s made with his iPad. The 288 foot long frieze is on view at Musee de l’Orangerie in Paris, celebrating the changing seasons in Normandy, where he spent lockdown painting.

Painting by David Hockney

Painting by David Hockney We spoke to Maria Rose about her fascination for painting plein air;

“Painting outdoors for me is a way to connect with nature, light and my surroundings and to truly 'see' my subject. The act of trying to capture a moment transcends my busy mind. For that hour or two, I simply paint and respond.”

Painting by Maria Rose

What the artists say….

“Painting outdoors has always been an intensely joyful experience. But now there is this layer that makes it feel as though I’m there seeking medicine.” Jeremy Miranda

“Reality is so much more interesting than fictional painting in a studio,” Cabeza de Baca

“Hell yeah, I am a plein air cat, I’ve been doing it always, seriously since around 2006. Love the performative quality of it. Anselm Kiefer says there is no innocent landscape—and he is probably right. This plein air urge—it is almost the artist under the other artist who always wants to break free, the artist who just wants to go out in the weather and paint what there is. I love that approach. I’d forgotten how exciting and intuitive that was. For me, painting from life is incredibly freeing.” Ragnar Kjartansson

“Being outside in nature is a huge source of inspiration for me, and if you are patient and look with the right kind of eyes, there is so much to see. When you paint outside it is easier to experience true colours, light and tonal values in the landscape.” David DJ Johnson

“It’s good for your eyes, to really focus and look. It’s good for your heart and soul, to observe, listen to the rhythms of nature and still your mind. A splash of vivid colour on a fresh piece of paper, the warm sun on your back….it’s like magic.” Sarah Middleton

Enter Wimborne Plein Air here: https://ottergallery.co.uk/wimborne-plein-air/

Mark off the May Bank Holiday in your diary!

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied to communicate with you in accordance with our Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.